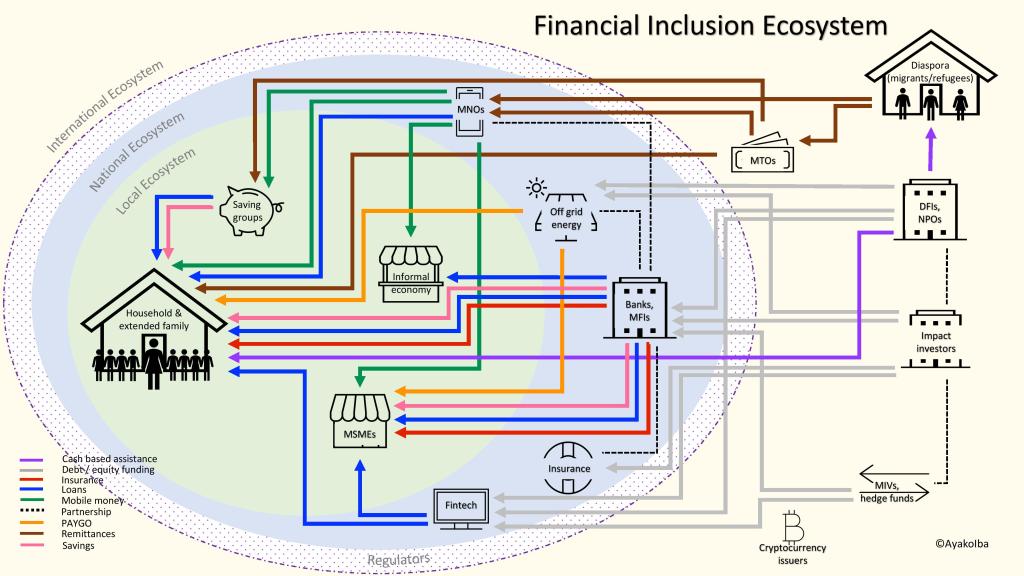

I am delighted to share my first attempt in putting together a diagram that represents the financial inclusion ecosystem.

While working in this sector and attending presentations provided by the different types of agencies I included here, I could not help but to notice that the linkages exist, but that the ecosystem continues to work as separate, rather detached clusters. This is why I wished to start putting the pieces together, to visualise the larger ecosystem and realise that we all work for the same end-goal; i.e. to foster financial inclusion of those who, historically or temporarily, have limited access to finance, so that they can become more economically sustainable and resilient.

For example, the main actors involved in improving the livelihoods of refugees – e.g. international non-profit organisations (NPOs) – which tend to focus on cash based assistance, have begun engaging with fintechs to digitalise the identification process, but are rarely in conversation about the role of remittances or saving groups at the local or diaspora level. Money transfer and mobile network operators (MTOs and MNOs) are actively engaging in conversations about remittances, but those that traditionally worked with microfinance institutions (MFIs) seem to not have yet found effective synergies to collaborate with them.

Before proceeding further, I would like to briefly explain the main aspects of this diagram. The green circle represents the local ecosystem or community, which – in very broad terms and specifically referring to financial inclusion – consists of the individual, its household, the extended families, the informal economy and MSMEs. At the national level, represented by the blue circle, different agencies operate, such as MNOs, off grid energy providers, banks and MFIs (including credit unions and other forms of legal entities), insurance companies and fintechs. The national financial ecosystem is often controlled, at least in part, by regulators, such as the central bank. However, this purple ring representing regulators is dotted, because depending on the legal form of the organisation, the latter may not be under any regulator’s scrutiny. In the international sphere, on one hand, there is the diaspora community – represented by migrants and refugees – who are commonly considered the main source of income for their families back home and send remittances via MTOs or other channels. On the other hand, there is a network of investors, ranging from development finance institutions (DFIs), impact investors and the intermediaries they use, such as microfinance investment vehicles (MIVs) and hedge funds. Lastly, each line represents a different type of financial service and its flow direction, while the dotted lines stand for common partnerships amongst the agencies.

Surely, this diagram is a working draft and it does not yet refer to some important actors of financial inclusion, such as those from the field of agricultural finance. Cryptocurrency is mentioned but without a defined link yet, since so far, there are only signs of people testing cryptocurrency platforms to send remittances. Nonetheless, I believe a visual, such as this diagram, helps to keep a customer-centric perspective of the ecosystem, which can support any of the actors involved in its processes for product development and also digitalisation. For example, the main target client, in this diagram, is represented by the house on the left, with its household and extended family, although the informal economy, MSMEs and the disapora community are part of the larger target group. When designing a new product or project for digitalisation, it is pivotal to understand which role you play in the larger ecosystem the target client inhabits and which services she or he is already using and through which channels.

With no further due for now, I very much welcome any feedback or thoughts from you!